It was thought-provoking when last week my excellent colleague Russel Tarr was accused by Secretary of State for Education Michael Gove of “infantilising” 14-year old students by asking them once they had finished studying the Weimar Republic, to re-present what they had learnt to younger 10-year old students in the form of their own Mr Men book.

It was thought-provoking when last week my excellent colleague Russel Tarr was accused by Secretary of State for Education Michael Gove of “infantilising” 14-year old students by asking them once they had finished studying the Weimar Republic, to re-present what they had learnt to younger 10-year old students in the form of their own Mr Men book.

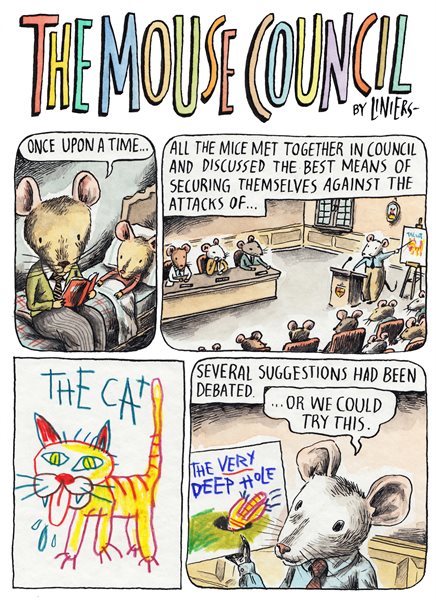

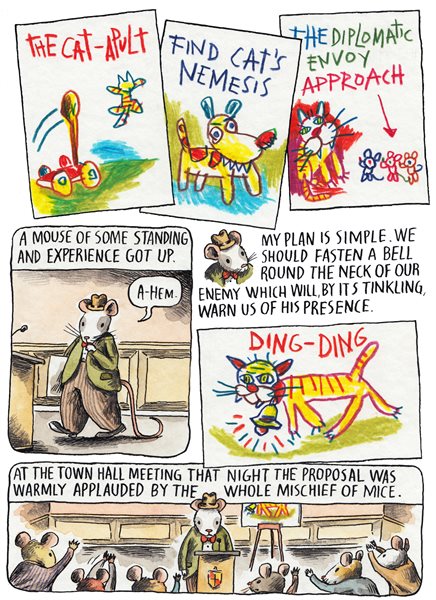

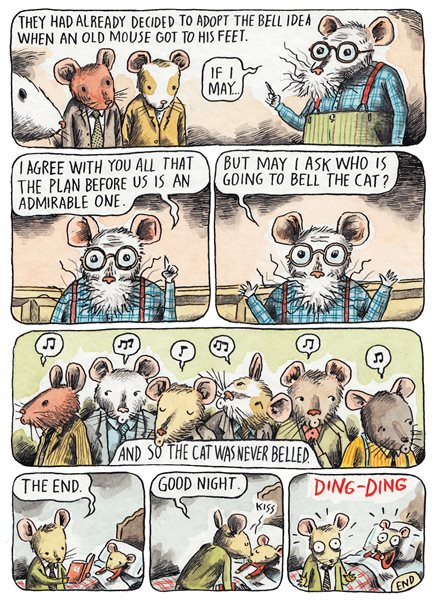

Russel answered the criticism very sufficiently on his popular history site activehistory.co.uk – but I’ve been thinking about one aspect of the business in particular: how and why we use fables.

Russel mentioned Orwell’s Animal Farm, but fables have a long history of being told to portray political events, though that’s may not be their only, or even main, purpose. The Kalilah and Dimnah fables of Persia for instance were in the frame story told by the sage Bidpai to a tyrant as a form of “mirror for princes”, a way to show things as they really were.

The oldest fable in the Bible is a political one, the fable of the Trees and the Brambles, given to discourage the people of Israel from adopting kingship:

One day the trees went out to anoint a king for themselves. They said to the olive tree, ‘Be our king.’ But the olive tree answered, ‘Should I give up my oil, by which both gods and humans are honored, to hold sway over the trees?’ Next, the trees said to the fig tree, ‘Come and be our king.’ But the fig tree replied, ‘Should I give up my fruit, so good and sweet, to hold sway over the trees?’ Then the trees said to the vine, ‘Come and be our king.’ But the vine answered, ‘Should I give up my wine, which cheers both gods and humans, to hold sway over the trees?’ Finally all the trees said to the thorn bush, ‘Come and be our king.’ The thorn bush said to the trees, `If you really want to anoint me king over you, come and take refuge in my shade; but if not, then let fire come out of the thorn bush and consume the cedars of Lebanon!’

One day the trees went out to anoint a king for themselves. They said to the olive tree, ‘Be our king.’ But the olive tree answered, ‘Should I give up my oil, by which both gods and humans are honored, to hold sway over the trees?’ Next, the trees said to the fig tree, ‘Come and be our king.’ But the fig tree replied, ‘Should I give up my fruit, so good and sweet, to hold sway over the trees?’ Then the trees said to the vine, ‘Come and be our king.’ But the vine answered, ‘Should I give up my wine, which cheers both gods and humans, to hold sway over the trees?’ Finally all the trees said to the thorn bush, ‘Come and be our king.’ The thorn bush said to the trees, `If you really want to anoint me king over you, come and take refuge in my shade; but if not, then let fire come out of the thorn bush and consume the cedars of Lebanon!’

A similar Aesop’s fables is said to have been delivered by Aesop to the Athenians for a political purpose too, the Frogs who Desired a King:

The Frogs, grieved at having no established Ruler, sent ambassadors to Jupiter entreating for a King. Perceiving their simplicity, he cast down a huge log into the lake. The Frogs were terrified at the splash occasioned by its fall and hid themselves in the depths of the pool. But as soon as they realized that the huge log was motionless, they swam again to the top of the water, dismissed their fears, climbed up, and began squatting on it in contempt.

After some time they began to think themselves ill-treated in the appointment of so inert a Ruler, and sent a second deputation to Jupiter to pray that he would set over them another sovereign. He then gave them an Eel to govern them. When the Frogs discovered his easy good nature, they sent yet a third time to Jupiter to beg him to choose for them still another King. Jupiter, displeased with all their complaints, sent a Heron, who preyed upon the Frogs day by day till there were none left to croak upon the lake.

After some time they began to think themselves ill-treated in the appointment of so inert a Ruler, and sent a second deputation to Jupiter to pray that he would set over them another sovereign. He then gave them an Eel to govern them. When the Frogs discovered his easy good nature, they sent yet a third time to Jupiter to beg him to choose for them still another King. Jupiter, displeased with all their complaints, sent a Heron, who preyed upon the Frogs day by day till there were none left to croak upon the lake.

So, why construct a fable? Why not just recount the situation literally, as it “actually is”?

I’m not sure what the whole answer is, but part of it is the power of storytelling to magnetise listeners. Another part is that you can put the actual historical people aside for one moment, with all the positive and negative associations and responses you have to them, while you look at the basic structure of events. And a third thing is that the act of making or recognising the metaphor allows you to see the whole thing newly, freshly and memorably.

Whether the characters in the metaphor are bushes, or frogs or characters from a children’s story is not important – it’s that their relationships and actions to each other hold up a mirror to human affairs. To object that a signifier is a children’s book character is to mistake the container and the content. It would be like objecting to Newton’s f=ma because it uses mere letters of the alphabet to represent physical forces. It’s the truth of the metaphor that’s important.

Now all three reasons for using fables seem to me to be excellent reasons for getting children to use a metaphor of some kind from time to time to deepen and share their understanding of events.

Now all three reasons for using fables seem to me to be excellent reasons for getting children to use a metaphor of some kind from time to time to deepen and share their understanding of events.

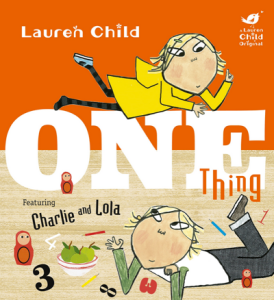

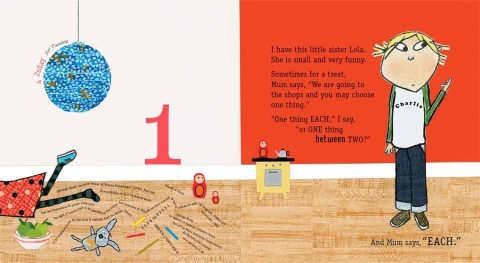

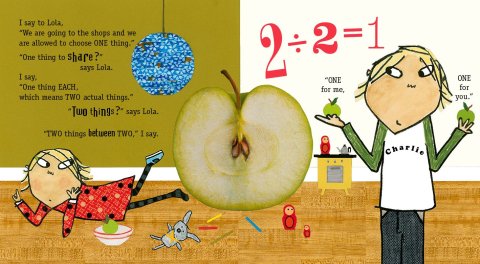

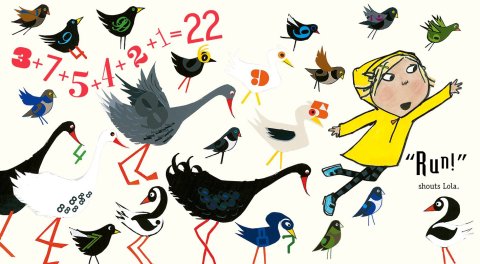

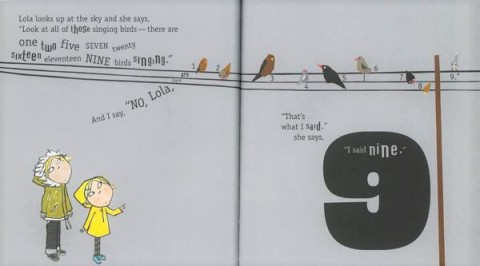

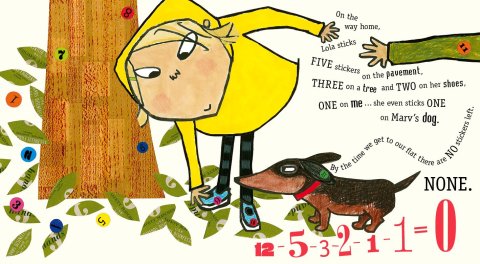

After five years, Lauren Child has published a new Charlie and Lola book, One Thing. It’s a book completely full of numbers. She says:

After five years, Lauren Child has published a new Charlie and Lola book, One Thing. It’s a book completely full of numbers. She says: It kicks off with mum saying they can have one thing from the shops. Is that one thing between two? Or one thing each?

It kicks off with mum saying they can have one thing from the shops. Is that one thing between two? Or one thing each?

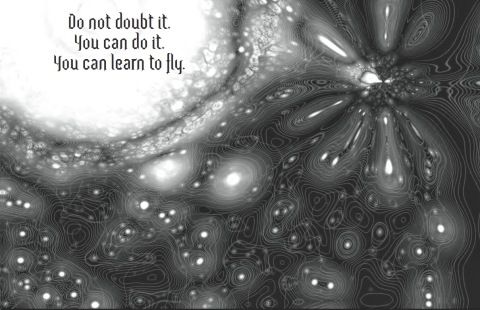

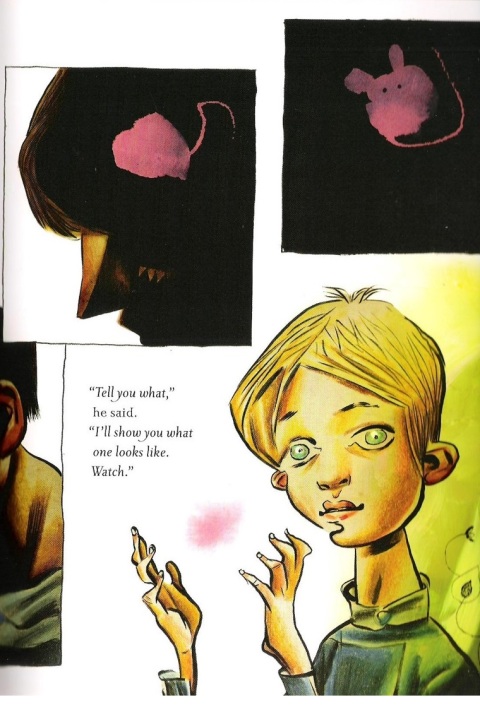

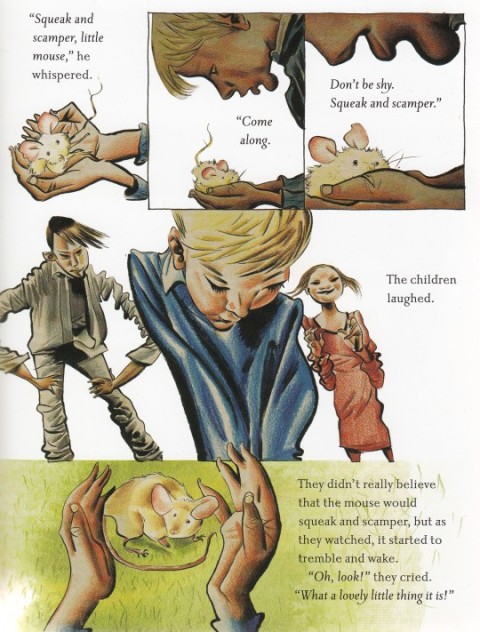

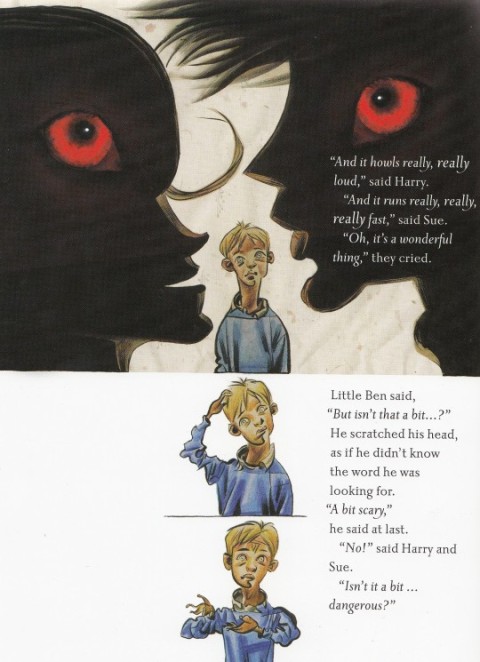

SF Said and Dave McKean teamed up for the brilliant Varjak books about a cat that learns who he really is, and who his friends are; Phoenix is their science fiction creation – and, for a child of, say, ten, what a great entry to the genre it is!

SF Said and Dave McKean teamed up for the brilliant Varjak books about a cat that learns who he really is, and who his friends are; Phoenix is their science fiction creation – and, for a child of, say, ten, what a great entry to the genre it is!

After some time they began to think themselves ill-treated in the appointment of so inert a Ruler, and sent a second deputation to Jupiter to pray that he would set over them another sovereign. He then gave them an Eel to govern them. When the Frogs discovered his easy good nature, they sent yet a third time to Jupiter to beg him to choose for them still another King. Jupiter, displeased with all their complaints, sent a Heron, who preyed upon the Frogs day by day till there were none left to croak upon the lake.

After some time they began to think themselves ill-treated in the appointment of so inert a Ruler, and sent a second deputation to Jupiter to pray that he would set over them another sovereign. He then gave them an Eel to govern them. When the Frogs discovered his easy good nature, they sent yet a third time to Jupiter to beg him to choose for them still another King. Jupiter, displeased with all their complaints, sent a Heron, who preyed upon the Frogs day by day till there were none left to croak upon the lake. Now all three reasons for using fables seem to me to be excellent reasons for getting children to use a metaphor of some kind from time to time to deepen and share their understanding of events.

Now all three reasons for using fables seem to me to be excellent reasons for getting children to use a metaphor of some kind from time to time to deepen and share their understanding of events.